The hype around “prompts”

In recent months, almost every lawyer has heard it somewhere: “You need to learn prompting.” There are workshops, cheat sheets, LinkedIn threads. Everyone has a tip: be as specific as possible, use personas, always ask for alternatives. All useful. But what often gets overlooked is that writing a really good prompt is a skill in itself, with a serious learning curve. You have to learn which context to include, how to clearly define your goal, role, tone and constraints – and then fully write that out again for every new case. That takes time, every single time. That is exactly where the difference lies between using a generic AI, where you manually redo that exercise for each matter, and using a legal AI platform where those prompts are already embedded in fixed workflows. For a firm working with real case files, that distinction is crucial.

What actually makes a prompt ‘good’?

In theory, a good prompt is fairly easy to define. It contains at least four elements. First, the goal: what exactly should the AI do? For example: “Give an objective summary of the opposing party’s submission, without rebuttal, in continuous prose.” Then the context: which case is this, at what stage of the legal process are you, which parties and facts are involved? For example: “This is a dispute between a carrier and a shipper concerning damage to goods during international road transport under the CMR Convention. This document is the formal notice of default from the shipper.” Next comes the format: what should the output look like – a single paragraph, a short memo, an email to the client, a paragraph that can be pasted directly into a brief. And finally, tone and role: who are you “being” and for whom are you writing? For example: “You are writing as a Belgian lawyer, in formal legal language, clear and precise, in Dutch.”

If you explicitly include all those elements in your prompt, you will often get strong output, even in a generic AI. So it absolutely makes sense for lawyers to understand how such a prompt is structured, and what the difference is between a vague question and a clear instruction. The problem is that this ideal quickly runs into the reality of a busy legal practice.

The perfect prompt idea collides with practice

In practice, you work with dozens of documents, you are behind on deadlines, and you are constantly switching between calls, emails, letters, writs of summons and trial briefs. There is little room to calmly write half a page of instructions such as: “You are a Belgian lawyer specialised in X, you receive document Y, do Z, only use sources from …”. Inevitably you use a shortcut: you copy an old prompt, tweak it, forget a nuance or a limitation. The output might still be good, but it becomes unpredictable. On top of that, this “prompt know-how” is usually personal: it sits in one partner’s head, in a Word document on someone’s desktop, or in a random chat history with ChatGPT. Colleagues and trainees use different variants, leave out crucial restrictions (“only use facts from the case file”), and it becomes impossible to reconstruct which exact prompt led to that one strong piece of text. At that point, prompting is no longer part of your firm’s process, but of individual improvisation.

When generic AI becomes a risk

There is a third problem: the risk of errors and hallucinations. A generic AI knows nothing about your quality standards, your library, or your constraints at case level. A prompt that is even slightly too loose – “Write a legal argument in favour of my client” – can lead to invented case law, doctrine that doesn’t exist, or propositions that are not supported by the evidence in the file. Of course you can correct that as a lawyer, but then you are essentially doing extra work on top of what you already had to do without AI.

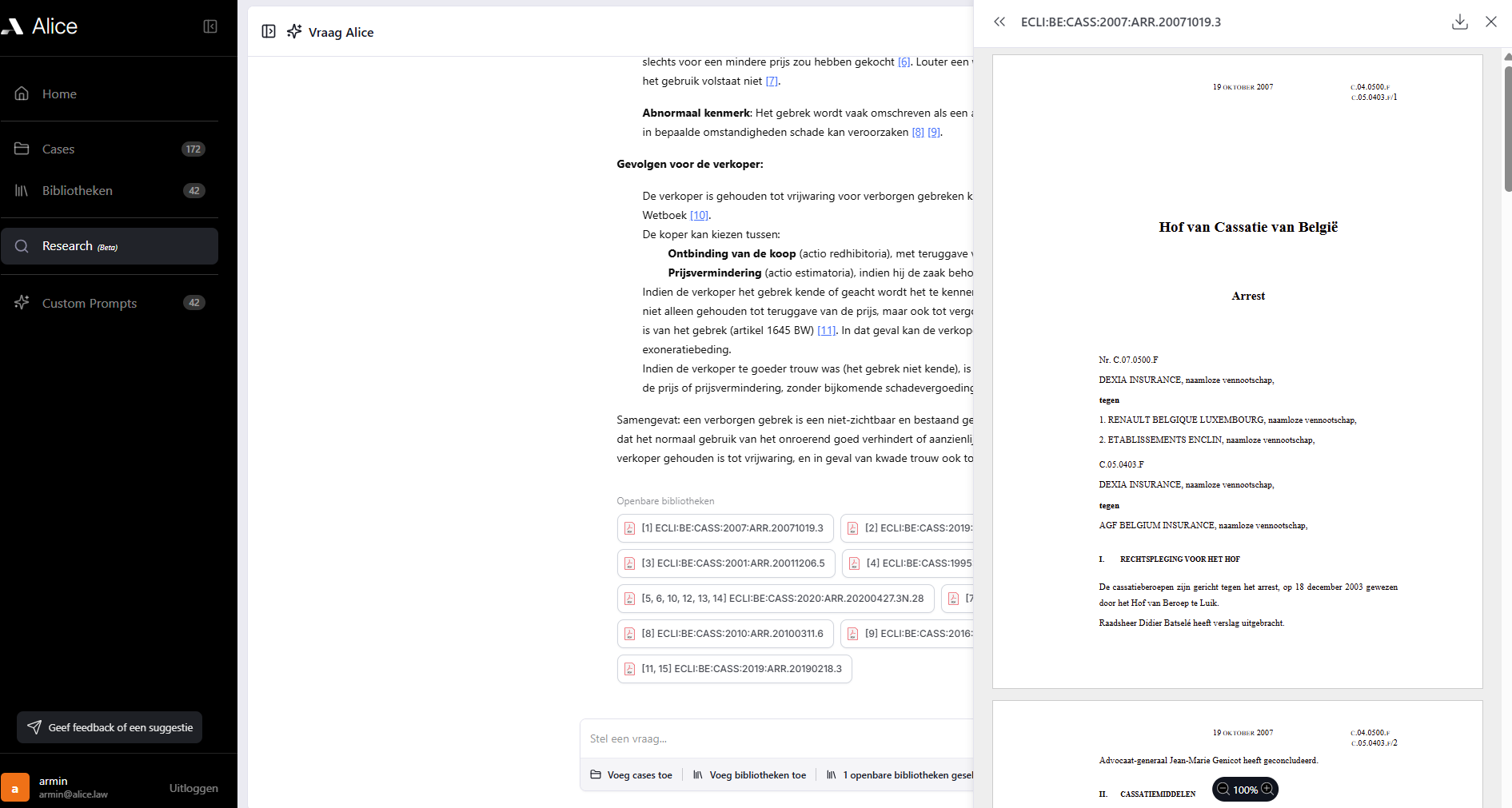

How a legal AI platform captures prompting in workflows

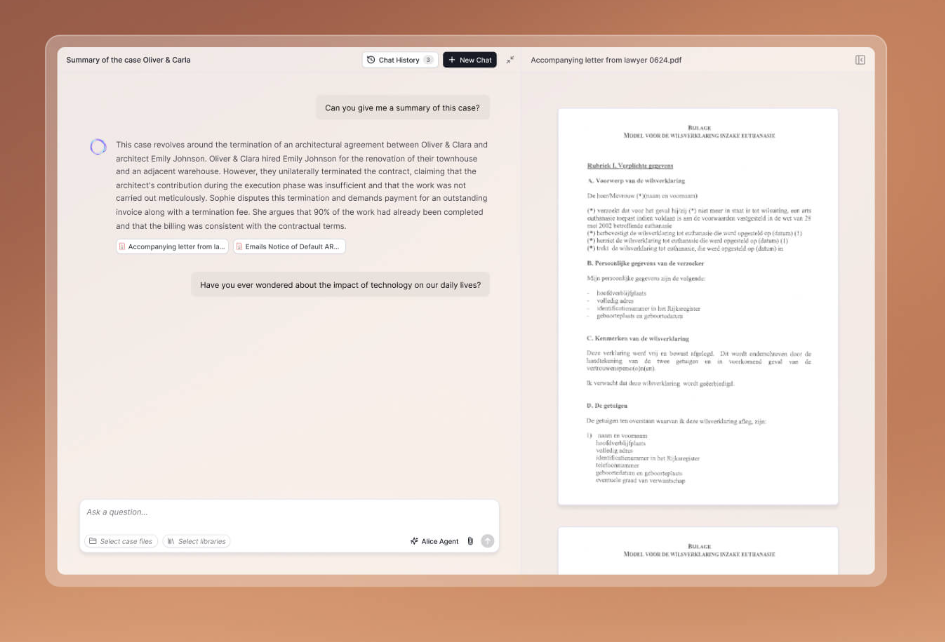

That is exactly where a legal AI platform like Alice takes a different path. Alice is not “ChatGPT in a nicer wrapper.” Under the hood you won’t find loose, ad hoc prompts, but carefully designed legal workflows. Where in a generic AI you have to spell everything out yourself, in Alice most of the work happens through the interface. You don’t start from a blank prompt field, but by choosing a workflow: case analysis, reconstruction of the opposing party’s position, argumentation in favour of the client, or drafting a legal document. You upload your case documents – submissions, judgments, contracts, emails – and indicate what you need: a paragraph for a brief, a memo, an email to the client, an internal summary.

In the background, Alice doesn’t send the AI a single loose prompt, but a chain of considered prompts: first, an analysis of the facts and procedural posture, then a link to relevant legal sources from the library, next the construction of the argumentation, and only then the generation of text. The persona – for example “Belgian lawyer before Court X” – is embedded in the workflow. The context comes directly from the uploaded case documents instead of vague descriptions. The structure of the output (headings, order, style) is predefined in templates that are aligned with practice. And the constraints – no invented case law, references only to sources in the selected libraries, no facts that do not appear in the case file – are built-in guardrails rather than optional advice.

What does (and doesn’t) change for the lawyer?

That does not mean prompting “disappears.” The level simply shifts. In a generic AI, you have to think up the entire prompt yourself every time, remember which elements need to be in it, and the quality depends on your time, focus and discipline at that moment. In Alice, the main prompts are well designed for each aspect, tested on real cases, and laid down as workflows. They are tuned to how litigators actually work: analysis → research → argumentation → document generation. You use them through buttons, fields and choices instead of long blocks of text.

The role of the lawyer does not change, but becomes sharper. You still have to set the objectives in the case: what exactly do we want to achieve at this stage? You choose which workflow fits: do we need a neutral case analysis, a partisan argument, a client-friendly explanation, or a fully drafted paragraph for a brief? And you remain ultimately responsible for evaluating the output: is the reasoning sound, does it align with our strategy, is it complete, should the tone be sharper or softer? You do not become a “prompt engineer”; you remain what you always were: a legal strategist – only now there is a platform beside you that accelerates, structures and makes the reasoning traceable.

Prompting as a foundation, workflows as the firm’s backbone

Does that mean being good at prompting becomes unnecessary? Definitely not. A basic understanding of prompting remains useful, for example to use generic tools smartly for non-matter work (marketing, internal memos, brainstorming, training), to understand what is happening under the hood of a platform like Alice, and to refine output (“rework §2 with more emphasis on causation”, “now create a shorter version for the client in plain language”). But once you are working with real cases, real risk and a team, you want to avoid the quality of your AI support depending on individual prompt creativity. At that point, you are better served by standardised workflows, reproducible quality and clear boundaries around sources, facts and style.

A mature strategy for a modern law firm combines both levels. Everyone understands the basic principles of prompting – goal, context, format, role – so people intuitively feel when something is “off.” At the same time, Alice takes over the heavy prompting work in pre-built workflows that do exactly what litigators need: analyse case files, bring relevant legal sources into context, build argumentation and generate legal documents. At firm level, you make clear agreements on which workflows to use when, and how the output is reviewed and refined.

That way, you combine the best of both worlds: the flexibility of language-based AI with the certainty and reproducibility of a legal AI platform built around the logic of legal work. Understanding prompting remains important. But the real step-change for the firm comes when you no longer rely on individual prompts, but on a platform where the key prompts and lines of reasoning have already been pre-built for you.

Meet a new way of working with AI

By lawyers, for lawyers

.jpg)